Portside Date:

November 23, 2017

Date of Source:

Wednesday, November 15, 2017

Portside

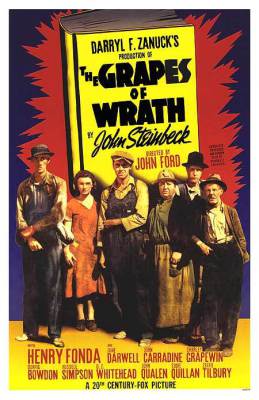

Steinbeck is most known for his iconic novel, The Grapes of Wrath, 1939, which described in detail the migration of the Joad family from their dust storm devastated farm land to California seeking work and eventually, they hoped, to accumulate enough money to buy land in this presumed mecca. Their travels involved encounters with thousands of other migrants, called "Okies," desperately leaving their homelands in several Southern and Midwest states to find a livelihood. The metaphor that shapes our consciousness of the suffering of the Great Depression of the 1930s, scholar Michael Denning suggests, is a natural disaster, the Dust Bowl.

But the natural disaster is in fact a part of a long history, political economy, politics and culture. New agricultural technologies, shifted the means of production and the products produced making small farming obsolete. This and a debt system that kept tenant farmers in bondage all created an inextricable connection between a crisis-prone capitalist political economy and the delicate balance of the natural environment.

Corporate land owners demanded that tenant farmers produce more cotton and wheat from land that had been overworked and when those farmers could not produce enough to pay their debts, tractors came and plowed under fences, farmhouses, and ways of life. In fact, the new mechanized agriculture did not need as many tenant farmers to grow the crops that fed the nation. So between the erosion of the land, the huge winds that blew the dusty soil all across the sky, the new agriculture, the debt system millions were set afoot. The deeply indebted tenant farmers forced off their land and enticed by advertisements promising work and wealth in California began the long migrations from Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas and elsewhere via old dilapidated trucks and cars to California.

We're sorry, said the owner men. The bank, the fifty-thousand-acre owner can't be responsible. You're on land that isn't yours. Once over the line maybe you can pick cotton in the fall. Maybe you can go on relief. Why don't you go on west to California? There's work there. And it never gets cold. Why, you can reach out anywhere and pick an orange. Why, there's always some kind of crop to work in. Why don't you go there? And the owner men started their cars and rolled away.[1]

Steinbeck powerfully describes the trek westward, the expenditures of life savings, the prejudices of gas station owners and other merchants against the "okies" along the way, the inspiring desperate efforts of migrants to share their meager food with others and the shocking arrival in a California where migrant labor is cheap and expendable. Grandpa and Pa Joad die along the way. Tom the second oldest son, and a recently paroled killer, joins a California labor struggle along the way and kills a sheriff in a brawl and is forced to leave the family. Tom tells his mother of his decision (powerfully recited by Henry Fonda in the movie version) after she asks how she will know about him. Tom Joad responds:

Well, maybe like Casy says, a fella ain't got a soul of his own, but on'y a piece of a big one-an' then-

.....I'll be ever'where-wherever you look. Wherever they's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever they's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there....I'll be in the way guys yell when they're made an'-I'll be in the way kids laugh when they're hungry an' they know supper's ready. An when our folks eat the stuff they raise an' live in the houses they build-why I'll be there.[2]

.....I'll be ever'where-wherever you look. Wherever they's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever they's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there....I'll be in the way guys yell when they're made an'-I'll be in the way kids laugh when they're hungry an' they know supper's ready. An when our folks eat the stuff they raise an' live in the houses they build-why I'll be there.[2]

Seen the pitcher last night, Grapes of Wrath, best cussed pitcher I ever seen.

The Grapes of Wrath, you know is about us pullin' out of Oklahoma and Arkansas, and down south, and a driftin' around over state of California, busted, disgusted, down and out, and a lookin' for work.

Shows you how come us to be that a way. Shows the dam bankers men that broke us and the dust that choked us, and comes right out in plain old English and says what to do about it.

It says you got to get together and have some meetins, and stick together, and raise old billy hell till you get your job, and get your farm back, and your house and your chickens and your groceries and your clothes, and your money back.

Go to see Grapes of Wrath, pardner, go to see it and don't miss.

You was the star in that picture. Go and see your own self and hear your own words and your own song.[3]

Tom Joad got out of the old McAlester Pen;

There he got his parole.

After four long years on a man killing charge,

Tom Joad come a-walkin' down the road, poor boy,

Tom Joad come a-walkin' down the road.

Tom Joad, he met a truck driving man;

There he caught him a ride.

He said, "I just got loose from McAlester Pen

On a charge called homicide,

A charge called homicide."

That truck rolled away in a cloud of dust;

Tommy turned his face toward home.

He met Preacher Casey, and they had a little drink,

But they found that his family they was gone,

He found that his family they was gone.

He found his mother's old-fashion shoe,

Found his daddy's hat.

And he found little Muley and Muley said,

"They've been tractored out by the cats,

They've been tractored out by the cats."

Tom Joad walked down to the neighbor's farm,

Found his family.

They took Preacher Casey and loaded in a car,

And his mother said, "We've got to get away."

His mother said, "We've got to get away."

Now, the twelve of the Joads made a mighty heavy load;

But Grandpa Joad did cry.

He picked up a handful of land in his hand,

Said: "I'm stayin' with the farm till I die.

Yes, I'm stayin' with the farm till I die."

They fed him short ribs and coffee and soothing syrup;

And Grandpa Joad did die.

They buried Grandpa Joad by the side of the road,

Grandma on the California side,

They buried Grandma on the California side.

They stood on a mountain and they looked to the west,

And it looked like the promised land.

That bright green valley with a river running through,

There was work for every single hand, they thought,

There was work for every single hand.

The Joads rolled away to the jungle camp,

There they cooked a stew.

And the hungry little kids of the jungle camp

Said: "We'd like to have some, too."

Said: "We'd like to have some, too."

Now a deputy sheriff fired loose at a man,

Shot a woman in the back.

Before he could take his aim again,

Preacher Casey dropped him in his track, poor boy,

Preacher Casey dropped him in his track.

They handcuffed Casey and they took him in jail;

And then he got away.

And he met Tom Joad on the old river bridge,

And these few words he did say, poor boy,

These few words he did say.

"I preached for the Lord a mighty long time,

Preached about the rich and the poor.

Us workin' folkses, all get together,

'Cause we ain't got a chance anymore.

We ain't got a chance anymore."

Now, the deputies come, and Tom and Casey run

To the bridge where the water run down.

But the vigilante thugs hit Casey with a club,

They laid Preacher Casey on the ground, poor Casey,

They laid Preacher Casey on the ground.

Tom Joad, he grabbed that deputy's club,

Hit him over the head.

Tom Joad took flight in the dark rainy night,

And a deputy and a preacher lying dead, two men,

A deputy and a preacher lying dead.

Tom run back where his mother was asleep;

He woke her up out of bed.

An' he kissed goodbye to the mother that he loved,

Said what Preacher Casey said, Tom Joad,

He said what Preacher Casey said.

"Ever'body might be just one big soul,

Well it looks that a-way to me.

Everywhere that you look, in the day or night,

That's where I'm a-gonna be, Ma,

That's where I'm a-gonna be.

Wherever little children are hungry and cry,

Wherever people ain't free.

Wherever men are fightin' for their rights,

That's where I'm a-gonna be, Ma.

That's where I'm a-gonna be."

Paradoxically, John Steinbeck published his powerful novel of labor strife in a California apple orchard in 1936, three years before his more famous novel. In Dubious Battle is about Communist organizers trying to mobilize super-exploited apple pickers to strike for higher wages and the right to form a union. In Dubious Battle takes place in the aftermath of large-scale strikes all up and down the West Coast including a general strike by longshoremen in San Francisco. It was also at a time when the Communist Party USA was actively engaged in helping to build a new militant, largely industrial, labor movement. While the reader does not find out the outcome of the strike and the new young militant organizer Jim, working as an apprentice of the experienced Mac is killed by vigilantes, the narrative takes the effort and the party militancy seriously. It also addresses in depth the problematic tactical questions about how to build class consciousness, creating unity and willingness to struggle out of isolation and self-centeredness.

Near the end of the novel Mac, the Communist leader, is called upon to give a eulogy for Joy, a hapless working class activist who spent his life protesting and rallies and getting brutally beaten by police. Joy arrived in a trainload of scabs and almost immediately is shot and killed by the same vigilantes who later would kill Jim. Mac tells the assembled mourners about Joy:

"The guy's name was Joy. He was a radical! Get it? A radical. He wanted guys like you to have enough to eat and a place to sleep where you wouldn't get wet. He didn't want nothing for himself He was a radical!...D' ye see what he was? A dirty bastard, a danger to the government I don't know if you saw his face, all beat to rags. The cops done that because he was a radical. His hands were broke, an' his jaw was broke. One time he got that jaw broke in a picket line....He was dangerous-he wanted guys like you to get enough to eat....What are you going to do about it? Dump him in a mud-hole, cover him with slush. Forget him.[4]

[2] John Steinbeck, 572.

[3] Woody Guthrie from a column in People's World, 1940, reprinted in Woody Suez, New York, 1975, p.133.

[4] John Steinbeck, In Dubious Battle, Penguin books, London,2000, 254.

[Harry Targ is a Professor of Political Science at Purdue University. He is a co-chair of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism [1] (CCDS).]