Harry Targ

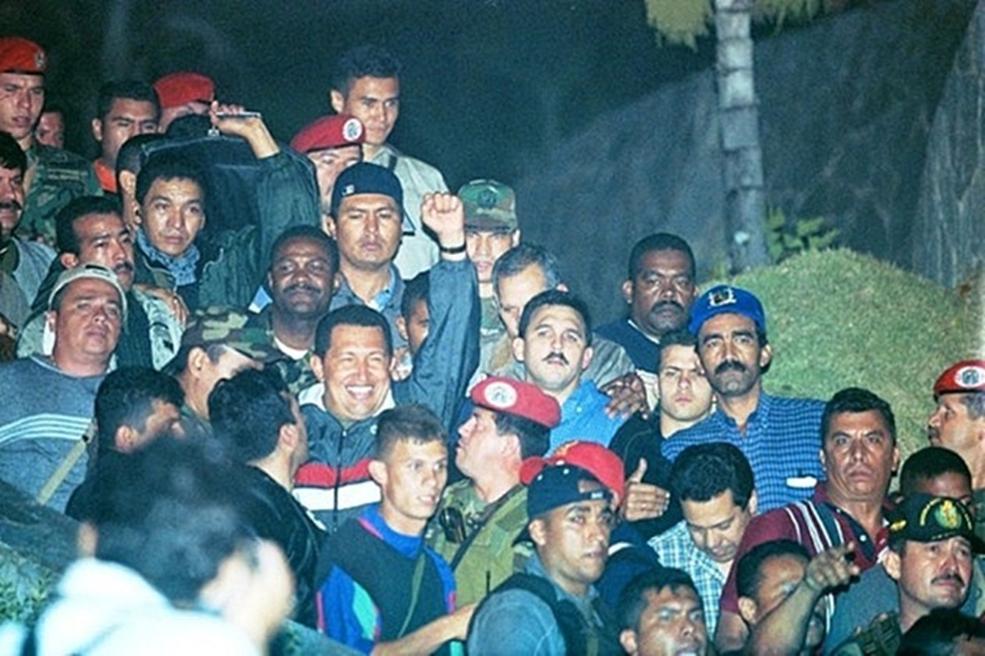

(Twenty years ago, April 11, 2002, sectors of the

Venezuela military, in conjunction with support from the United States,

launched a coup to oust former President Hugo Chavez from power in Venezuela.

But, as the image below suggests, the vast majority of the people said “no” to

the coup and they and most of the military released Chavez. Subsequently,

before his death from natural causes, Chavez inspired a “Pink Tide” to create

alternative economic and political institutions to challenge US hegemony in the

Western Hemisphere. While the road has been rocky, the spirit of Chavez

survives with the recent elections of progressives in Bolivia, Chile, Peru,

Argentina, Nicaragua, Honduras, Mexico, and the Cuban Revolution remains a beacon of

hope for the Global South).

A Brief History

As Greg Grandin argues in “Empire’s Workshop,” the

rise of the United States as a global empire begins in the Western Hemisphere.

For example, the Spanish/Cuban/American war provided the occasion for the

United States to develop a two-ocean navy, fulfilling Assistant Secretary of

the Navy Theodore Roosevelt’s dreams. After interfering in the Cuban Revolution

in 1898 defeating Spain, the United States attacked the Spanish outpost in the

Philippines, thus becoming a global power. Latin American interventionism throughout

the Western Hemisphere, sending troops into Central American and Caribbean

countries thirty times between the 1890s and 1933, (including a Marine

occupation of Haiti from 1915 until 1934), “tested” what would become after

World War II a pattern of covert interventions and wars in Asia, Africa, and

the Middle East.

The Western Hemisphere was colonized by Spain, Portugal, Great Britain, and France from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries. The main source of accumulated wealth that funded the rise of capitalism as a world system came from raw material and slave labor in the Western Hemisphere: gold, silver, sugar, coffee, tea, cocoa, and later oil. What Marx called the stage of “primitive accumulation,” was a period in world history governed by land grabs, mass slaughter of indigenous peoples, expropriation of natural resources, and the capture, transport, and enslavement of millions of African people. Conquest, land occupation, and dispossession was coupled with the institutionalization of a Church that would convince the survivors of this stage of capitalism’s development that all was “God’s plan.”

Imperial expansion generated resistance throughout this history. In the nineteenth century countries and peoples achieved their formal independence from colonial rule. Simon Bolivar, the nineteenth century leader of resistance, spoke for national sovereignty in Latin America.

But from 1898 until the present, the Western

Hemisphere has been shaped by US efforts to replace the traditional colonial

powers with neo-colonial regimes. Economic institutions, class systems,

militaries, and religious institutions were influenced by United States

domination of the region.

In the period of the Cold War, 1945-1991, the United States played the leading role in overthrowing the reformist government of Jacob Arbenz in Guatemala (1954), Salvador Allende in Chile (1973), and gave support to brutal military dictatorships in the 1970s in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Also, the United States supported dictatorship in Haiti from 1957 until 1986. The Reagan administration engaged in a decade-long war on Central America in the 1980s. In 1965 the United States sent thousands of marines to the Dominican Republic to forestall nationalist Juan Bosch from returning to power and in 1989 to overthrow the government of Manuel Noriega in Panama. (This was a prelude to Gulf War I against Iraq).

From 1959 until today the United States has sought through attempted military intervention, economic blockade and cultural intrusion, and international pressures to undermine, weaken, and destroy the Cuban Revolution.

Often during this dark history US policymakers have sought to mask interventionism in the warm glow of economic development. President Kennedy called for an economic development program in Latin America, called the Alliance for Progress and Operation Bootstrap for Puerto Rico. Even the harsh “shock therapy” of neoliberalism imposed on Bolivia in the 1980s was based upon the promise of rapid economic development in that country.

The Bolivarian Revolution

The 21st century has witnessed a variety of forms of

resistance to the drive for global hegemony and the perpetuation of neoliberal

globalization. First, the two largest economies in the world, China and

India, have experienced economic growth rates well in excess of the industrial

capitalist countries. China has developed a global export and investment

program in Latin America and Africa that exceeds that of the United States and

Europe.

On the Latin American continent, under the leadership and inspiration of former

President Hugo Chavez, Venezuela launched the latest round of state resistance

to the colossus of the north, with his Bolivarian Revolution. He planted the

seeds of socialism at home and encouraged Latin Americans to participate in the

construction of financial institutions and economic assistance programs to

challenge the traditional hegemony of the International Monetary Fund, the

World Bank, and the World Trade Organization.

The Bolivarian Revolution stimulated political change based on varying degrees

of grassroots democratization, the construction of workers’ cooperatives, and a

shift from neoliberal economic policies to economic populism. A Bolivarian

Revolution was being constructed with a growing web of participants: Bolivia,

Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and, of course,

Cuba.

It was hoped that after the premature death of Chavez in 2013, the Bolivarian Revolution would continue in Venezuela and throughout the region. But the economic ties and political solidarity of progressive regimes, hemisphere regional institutions, and grassroots movements have been challenged by declining oil prices and economic errors; increasing covert intervention in Venezuelan affairs by the United States; a US-encouraged shift to the right by “soft coups” in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador; and a more aggressive United States foreign policy toward Latin America. Governments supportive of Latin American solidarity with Venezuela were temporarily undermined and/or defeated in elections in Honduras, Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina, and attacks in the Trump period (but not reversed by President Biden) escalated against what Trump’s former National Security Advisor John Bolton called “the troika of tyranny;” Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba. As Vijay Prashad put it: “Far right leaders in the hemisphere (Bolsonaro, Márquez, and Trump) salivate at the prospect of regime change in each of these countries. They want to eviscerate the “pink tide” from the region” (Vijay Prashad, thetricontinental.org, January 20, 2019).

Special Dilemmas Latin Americans Face

Historically all Western Hemisphere countries have been shaped and distorted in their economies, polities, and cultures by colonialism and neo-colonialism. They have also been shaped by their long histories of resistance to outside forces seeking to develop imperial hegemony. Latin American history is both a history of oppression, exploitation, and violence, and confrontation with mass movements of various kinds. The Bolivarian Revolution of the twenty-first century is the most recent exemplar of grassroots resistance against neo-colonial domination. Armed with this historical understanding several historical realities bear on the current threats to the Venezuelan government.

First, every country, with the exception of Cuba, experiences deep class divisions. Workers, peasants, the new precariat, people of color, youth, and women face off against very wealthy financiers, entrepreneurs, and industrialists, often with family ties, as well as corporate ties, with the United States. Whether one is trying to understand the soft coup in Brazil, the instability in Nicaragua, or the deep divisions in Venezuela, class struggle is a central feature of whatever conflicts are occurring.

Second, United States policy in the administrations of both political parties is fundamentally driven by opposition to the full independence of Latin America. US policy throughout the new century has been inalterably opposed to the Bolivarian Revolution. Consequently, a centerpiece of United States policy is to support by whatever means the wealthy classes in each country.

Third, as a byproduct of the colonial and neo-colonial stages in the region,

local ruling classes and their North American allies have supported the

creation of sizable militaries. Consequently, in political and economic life,

the military remains a key actor in each country in the region. Most often, the

military serves the interests of the wealthy class (or is part of it), and

works overtly or covertly to resist democracy, majority rule, and the

grassroots. Consequently, each progressive government in the region has had to

figure out how to relate to the military. In the case of Chile, President

Allende assumed the military would stay neutral in growing political disputes

among competing class forces. But the Nixon Administration was able to identify

and work with generals who ultimately carried out a military coup against the

popular elected socialist government of Chile. So far in the Venezuelan case,

the military seems to be siding with the government. Chavez himself was a

military officer.

Fourth, given the rise of grassroots movements, the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela began to support “dual power,” particularly at the local level. Along with political institutions that traditionally were controlled by the rich and powerful, new local institutions of popular power were created. The establishment of popular power has been a key feature of many governments ever since the Cuban Revolution. Popular power, to varying degrees, is replicated in economic institutions, in culture, and in community life such that in Venezuela and elsewhere workers and peasants see their own empowerment as tied to the survival of revolutionary governments. In short, defense of the Maduro government, depends on the continuing support of the grassroots and the military.

Fifth, the governments of the Bolivarian Revolution

face many obstacles. Small but powerful capitalist classes is one. Persistent

United States covert operations and military bases throughout the region is

another. And, perhaps most importantly, given the hundreds of years of colonial

and neo-colonial rule, Latin American economies remain distorted by

over-reliance on small numbers of raw materials and, as a result of pressure

from international financial institutions, on export of selected products such

as agricultural crops. In other words, historically Latin American economies

have been distorted by the pressure on them to create one-crop economies to

serve the interests of powerful capitalist countries, not diversified economies

to serve the people.

Finally, and more speculatively, United States policy

toward the region from time to time is affected by the exigencies of domestic

politics. For example, each US administration has given undue attention to

rightwing pressures from powerful counter-revolutionary Cubans, mostly in

Florida. Foreign policy often is a byproduct of domestic politics.

Where do Progressives Stand

First, and foremost, progressives should prioritize an

understanding of imperialism, colonialism, neocolonialism, and the role of

Latin American as the “laboratory” for testing United States interventionist

foreign policies. This means that critics of US imperialism can be most

effective by avoiding “purity tests” when contemplating political activism

around US foreign policy. That is, the main task should be opposing US

intervention in the affairs of other countries not judging their institutions

and policies. One cannot forget the connections between current patterns of

policy toward Venezuela, with the rhetoric, the threats, the claims, and US

policies toward Guatemala, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Brazil,

Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Panama, and in the new century,

Bolivia, Venezuela, Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina.

Second, progressives need to show solidarity with grassroots movements in the region, support human rights, oppose military interventions, and demand the closure of the myriad of United States military bases in the region and end training military personnel from the region. (When citizens raise concerns about other countries interfering in the US political system, it is hypocritical for the United States to interfere in the political and economic lives of other countries in Latin America.).

Finally, progressives must oppose all United States foreign policies that are designed to maintain twenty-first century forms of imperialism in the Western Hemisphere. Support for progressive candidates for public office should require that they oppose economic blockades, punishing austerity programs imposed by international financial institutions, the maintenance of US ties with ruling classes in the region; essentially all forms of interference in the economic and political life of the region. And, as progressives correctly proclaim about domestic life, their candidates should be in solidarity with the poor, oppressed, and marginalized people of the Western Hemisphere. Progressives cannot with integrity support the “99 percent” in the United States against the “1 percent” without giving similar support for the vast majority of workers, farmers, women, people of color, and indigenous people throughout the hemisphere.

And if it is true that US policy toward Latin America is a laboratory for its policy globally, the same standard should be applied to United States policy globally.

The time has come for the articulation of a comprehensive stand against United States imperialism in the Western Hemisphere, and around the world.

-A useful history of United States interventionism can

be found in Stephen Kinzer, Overthrow: America’s Century of

Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq, Henry

Holt, 2006.

-On the anniversary of the Venezuelan coup attempt see: