Harry Targ

A

Reuters report on the weekend meeting of the G77 plus China in HAVANA:

Closing Statement Issued by the Group of 77

A Radio Conversation about the Global

South:

****************************************************************************

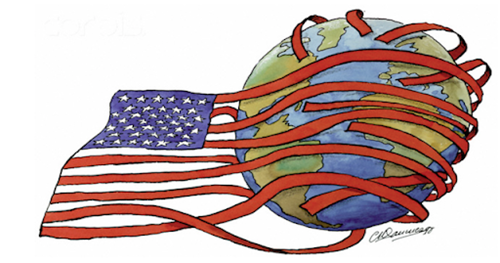

THE REALITIES OF

IMPERIALISM AND DEPENDENCY: STILL RELEVANT TODAY

Council on Foreign Relations, October 31,

2022

Leftist former President Luiz Inácio Lula

da Silva, commonly known as Lula, won

Brazil’s presidential runoff (Reuters) yesterday,

defeating incumbent Jair Bolsonaro by less than two percentage points.

Bolsonaro did not concede the election last night nor make any public

statement. Heads of state from around the world congratulated Lula on

his victory.

Imperialism

Students of imperialism appropriately refer to the

polemical but theoretically relevant essay authored by Marx and

Engels, The Communist Manifesto. In this essay, the authors argue that

capitalism as a mode of production is driven to traverse the globe, for

investment opportunities, for cheap labor, for natural resources, for land. One

can argue that Marx and Engels were among the first to theorize about

globalization.

Lenin advanced the theory of imperialism in his famous

essay Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. In addition to

the inspiration from Marx and Engels, he drew from the sophisticated writings

of Rudolf Hilferding and John Hobson. For him, writing in the midst of the

bloodshed of World War I and revolutionary ferment in Russia, there was a need

to understand the connections between the expansionist needs of capitalism,

competition among capitalist states, and imperialist war. With that motivation,

Lenin postulated five key features of what he called imperialism, the highest

stage of capitalism. This new stage of capitalist development in the twentieth

century included:

1) The concentration of production and capital

developed to such a high stage that it created monopolies, which play a

decisive role in economic life.

2) The merging of bank capital with industrial

capital, and the creation, on the basis of this, "finance capital,"

or a "financial oligarchy."

3) The export of capital, which has become extremely

important, as distinguished from the export of commodities.

4) The formation of international capitalist

monopolies, which share the world among themselves.

5) The territorial division of the whole world among

the greatest capitalist powers is completed.

Lenin’s descriptions of these five features of

twentieth century imperialism were prescient as to their long-term vision.

Imperialism was not just a way in which powerful states acted in the world but

a global stage of capitalism. The political, military, and economic dimensions

of the world were inextricably connected in a profoundly new way, different

from prior periods of human history.

In this stage national economies and the global

economy were dominated by monopolies. That is, small numbers of banks and

corporations controlled the majority of the wealth and productive capacity of

the world. (The Brandt Commission in the early 1980s estimated, for example,

that 200 corporations and banks controlled twenty-five percent of the world’s

wealth). Monopolization included a shrinking number of economic actors that

controlled larger and larger shares of each economic sector (steel, auto, fossil

fuels, for example) and fewer and fewer actors controlling more of the totality

of all these sectors.

Lenin added that twentieth century finance capital

assumed a primary role in the global economy compared to prior centuries when

banks were merely the bookkeepers of the capitalist system. Corporate capital

and financial capital had become indistinguishable. This, in our own day,

became known as "financialization.”

The development of finance capital, Lenin argued, led

to the export of capital, the promotion of investments, the enticement of a

debt system, and the expanding control of all financial transactions by the few

hundred global banks. Capitalism was no longer just about expropriating labor

and natural resources, processing these into products for sale on a world

market but it now was about financial speculation, the flow of currencies as

much as the flow of products of labor. It was in this stage of capitalism that

the financial system was used as a lever to transform all of the world’s

economies, particularly by increasing profits through imposing policies of

austerity. Austerity included cutting government programs, deregulating

economies so banks and corporations could act more freely, and, further,

instituting public policies to maximize the privatization of virtually every

public institution. Also, and of particular relevance to the Brazilian case,

was the opening up of natural resources and land to global corporations. These

policies were referred to as “neoliberal.”

And lastly, Lenin observed, world politics was shaped

by economic and political collusion of international monopolies to collaborate,

routinize, and regulate economic competition. But, as he saw in 1916, that

world of routinized global finance capital had broken down, states representing

their own financial conglomerates engaged in massive violence, in World War, to

maintain their share of territory and wealth. So that imperialism, the highest

stage of capitalism, always had embedded within it, the seeds of ever-expanding

war between states driven by their own monopolies.

Dependency

Theorists and revolutionaries from the Global South found Lenin’s theory of imperialism to be a compelling explanation of the historical development of capitalism as a world system and its connections to war, violence, colonialism, and neo-colonialism. However, they argued that Lenin’s narrative was incomplete in its description of imperialism’s impact on the countries and peoples of the Global South. Several revolutionary writers and activists from the Global South added a “bottom up” narrative about imperialism. Theorists such as Andre Gunter Frank, Samir Amin, Frantz Fanon, Walter Rodney, Fernando Cardoso, Theotonio Dos Santos, and Jose Carlos Mariategui added an understanding of “dependency” to the discussion of imperialism. And today the writings of V J Prashad and his colleagues at Tricontinental carry on the tradition.

Dependency theorists suggested that the imperialist

stage of capitalism was not enforced in the Global South only at the point of a

gun. Dependency required the institutionalization of class structures in the

Global South. Ruling classes in the Global South, local owners of factories,

fields, and natural resources, and their armies, collaborated with the ruling

classes of the global centers of power in the Global North. In fact, the

imperial system required collaboration between ruling classes in the global

centers with ruling classes in the periphery of the international system. And

ultimately, imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism, was a political and

economic system in which the ruling classes in the centers of power worked in

collaboration with the ruling classes in the Global South to exploit and

repress the vast majority of human beings in the world.

Dependency theory, therefore, added insights to the

Leninist analysis. First, the imperial system required collaboration from the

rich and powerful classes in the centers of global power, the Global North,

developing and recruiting the rich and powerful classes in the countries of the

Global South. It also meant that there was a need to understand that the

imperial system required smooth flows of profits from the Global South to the

Global North. Therefore, there was a mutuality of interests among ruling classes

everywhere. The addition of dependency theory also argued that people in the

periphery, workers and peasants in poor countries, had objective interests not

only opposed to the imperial countries from the north but to the interests of

their own national ruling classes. And, if this imperial system exploited

workers in the centers of power and also in the peripheral areas of the world,

then there ultimately was a commonality of interests of the poor,

oppressed, and exploited all across the face of the globe.

Relevance for the Twenty-First Century

Although the world of the twenty-first century is

different from that of the twentieth century, commonalities exist. These

include the expansion of finance capital, rising resistance to it everywhere,

and conflicts in the Global North and the Global South between powerful ruling

classes and masses of people seeking democracy and economic well-being. In the

recent past, the resurgence of protest by workers, students, farmers and

peasants, the popular classes, has been reflected in mass movements against neoliberal

globalization and international financial institutions. These include Arab

Spring, the Fight for Fifteen, and a number of campaigns that challenge racism,

sexism, joblessness, the destruction of the environment, land grabs, and

removal of indigenous peoples from their land. The electoral victory of Lula is

the most recent example.

In Latin America, movements emerged that have been

labeled “the Pink Tide” or the “Bolivarian Revolution.” These are movements

driven by struggles between the Global North and the Global

South and class struggles within countries of the Global South.

Workers and peasants from the Global South have been motivated to create,

albeit within powerful historical constraints, alternative economic and

political institutions in their own countries. The awakening of the masses of

people in the Global South constitute one of the two main threats to

Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. The first threat is the movements

that are struggling to break the link between their own ruling classes and

those of the North. That includes working with leaders who are standing up

against the imperial system (leaders such as in Venezuela, Bolivia, and, of

course Cuba). The other threat to Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism,

is, as Lenin observed in 1916, war between imperial powers.

In sum, as activists mobilize to oppose US war against

the peoples of Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, it is critical

to be aware of the imperial system of finance capital, class systems in the

Global North and Global South, and to realize that solidarity involves

understanding the common material interests of popular classes in both the

Global North and South. In 2022, solidarity includes opposing United States

militarism in Latin America, economic blockades against peoples seeking their own

liberation, and covert operations to support current and former ruling classes

in their countries that collaborate with imperialism.

Concretely, this means supporting the Bolivarian

Revolution in Venezuela and throughout the Western Hemisphere, protests in

Haiti, of course, the Cuban Revolution, and now the transition to democracy in

Brazil.

https://heartlandradical.blogspot.com/2022/10/how-world-is-framed-spokespersons-from.html

***************************************************************************************

THE UNITED STATES

OVERTHROWS ALLENDE BUT THE GLOBAL SOUTH CONTINUES TO ORGANIZE

A Radio Conversation About the Overthrow

of Allende and Its Long-Term Consequences

The Allende Years and the US Coup

National Security Archive

The election of Socialist Salvador Allende in Chile in

1970 became the target of sustained interest of the Nixon Administration. The

United States had supported the Christian Democrats in Chile with official

assistance and CIA financing since the 1950s. Eduardo Frei, Chile's president

from 1964 to 1970, had been its favorite Chilean politician. Frei had been

opposed in presidential elections by the Marxist Allende, who, leading a left

coalition, finally won a plurality of votes in 1970, despite much CIA money

funneled into the coffers of the Christian Democratic candidate. From the time

of the election in October, 1970, until September, 1973, when a bloody military

coup toppled Allende, the United States did everything it could to destabilize

the elected government. From October to November, 1970, the United States

pressured members of the Chilean parliament to vote against certification of

the election victory, traditionally a routine exercise.

After Allende had been confirmed as president, energy

and resources were used to damage the economy and make contact with right-wing

members of the Chilean military to plan a coup. Allende carried out many

policies designed to improve the material conditions of the lives of the

workers and peasants in Chile. Land was redistributed, major industries were

nationalized (copper had been partially nationalized under Frei), and diplomatic

relations were established with the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba. All these

moves exacerbated tensions with the United States, since investments in copper,

iron, nitrates, iodine, and salt were large.

The Nixon administration formed a secret committee, headed by Kissinger and enthusiastically endorsed by the International Telephone and Telegraph Company, a major economic power in Chile, whose purpose was the overthrow of Allende. The committee's preference was for an Allende defeat resulting from public rejection, but, if all else failed, a military coup was preferable to a continuation of his government. Among the policies utilized by Washington were an informal economic blockade of Chile, termination of aid and loans, IMF pressure on the government to carry out antiworker policies, fomenting dissent in the military, and funding opposition groups and newspapers, like the influential newspaper El Mercurio.

Allende's economic policies were effective and generated much support from workers and peasants during 1970 and 1971; but, after the economic squeeze on the government increased, Allende had to grapple with inflation, balance-of-payments problems, and the inability to get spare parts and capital goods that had traditionally come from the United States. In trying to forestall military intervention in the political process, Allende allowed the "constitutionalist" officers to be replaced by avowed fascist generals. U.S. contacts with these generals provided the organizational basis for the impending coup. Excessive demands by more well paid workers and more secure peasants, coupled with a truckers' strike and demonstrations of middle-class housewives organized by the rightwing, added to the problems of the Allende government in 1972 and 1973. Despite the increasing economic and political problems being faced by Allende and the systematic efforts by the U.S. government to create discord within Chile, the Allende-led left coalition scored electoral victories in municipal elections throughout the country in March, 1973.

Since "making the economy scream" had not led to the rejection of Allende at the ballot box, the Kissinger committee and the right-wing generals decided to act. On September I l, 1973, the military carried out a coup that ousted the Allende government, and Allende himself was assassinated in the presidential palace. A junta headed by General Pinochet began a policy of extermination, torture, and imprisonment on a massive scale. A year after the coup, Amnesty International reported that some 6,000 to 10,000 prisoners had been taken. The new regime also banned all political parties, abolished trade unions, and continued its political repression both at home and abroad. In reference to the latter, Orlando Letelier, foreign minister in the Allende government, was blown up in a car in Washington, D.C., by Pinochet agents.

Socialist Worker.org

The spirit of the brutal U.S. policy in Chile was expressed by Kissinger in 1970: "I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people" (James A. Nathan and James K. Oliver, United States Foreign Policy and World Order, Little, Brown, 1981, p.496) and by President Ford in his first press conference, defending the coup as being in the "best interests of the people of Chile and certainly in the best interests of the United States" (Nathan and Oliver, p. 497). A somewhat more accurate assessment was made by historian Alexander De Conde, who wrote that the United States “had a hand in the destruction of a moderate left-wing government that allowed democratic freedoms to its people and to its replacement by a friendly right-wing government that crushed such freedoms with torture and other police-state repressions" (Alexander DeConde, A History of American Foreign Policy, Volume ll Charles Scribner, 1978, pp.388-389).

The Third World Demands a New

International Economic Order

The brutal overthrow of the Allende government

in Chile was reminiscent of traditional US. activities as world policeman. The

impact of the coup on the Chilean people in terms of economic justice and

political freedom was negative in the extreme. The bloody victory of

counterrevolution in Chile, however, came at a period in world history when the

rise of Third World resistance to U.S. imperialism would reduce the prospect of

more Chiles in the future.

By the 1970s, the worldwide resistance to U.S.

and international capitalism was growing. The revolutionary manifestation of

this resistance was occurring in Southeast Asia, southern Africa, the Horn of

Africa, the Middle East, and Central America and the Caribbean. During the

Nixon-Ford period, the United States and its imperialist allies lost control of

the Indochinese states, Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. South Yemen,

Nicaragua, Iran, and Grenada would follow later in the decade.

The Progressive International

Along with the rise of revolutionary victories and

movements throughout the Third World, a worldwide reformist movement began to

take shape around demands for a New International Economic Order (NIEO). Its

predecessor, the. nonaligned movement of the 1950s and 1960s, had been nurtured

by leading anticolonial figures such as Nasser of Egypt, Nkrumah of Ghana, and

Nehru of India. Their goal was to construct a bloc of Third World nations of

all ideological hues which could achieve political power and economic advantage

by avoiding alliances and political stances that might tie them to the United

States or the Soviet Union. The nonaligned movement saw the interests of member

nations tied to the resolution of "north-south" issues, which in

their view were of greater importance than "east-west" issues.

After two decades of experience with political

independence from formal colonialism, revolutionaries who believed that

economic exploitation resulted from the structure of the international

capitalist system were joined by Third World leaders who saw the need to reform

international capitalism. Consequently, a movement emerged, largely within UN

agencies, increasingly populated by Third World nations and addressing itself

to Third World poverty and underdevelopment. This movement presupposed the

possibility of reducing the suffering of Third World peoples without

necessarily bringing an end to capitalism as the internationally dominant mode

of production.

To counter the declining Third World percentage of

world trade, fluctuations in prices of exported commodities, foreign corporate

repatriation of profits earned in Third World countries, technological

dependence, growing international debt, and deepening crises in the supply of

food, Third World leaders were forced by material conditions and revolutionary

ferment to call for reforms. The inspiration for a NIEO movement came also from

the seeming success of OPEC countries in gaining control of oil pricing and

production decisions from foreign corporations.

Two special sessions of the General Assembly of the UN

in 1974 and 1975 on the NIEO "established the concept as a priority item

of the international community" (Ervin Laszlo, Robert Baker Jr., Elliott

Eisenberg, Raman Venkata, The Objectives of the New

International Economic Order, New York, Pergamon, 1978, pp. xvi). The NEIO

became a short-hand reference for a series of interrelated economic and

political demands concerning issues that required fundamental policy changes,

particularly from wealthy nations. The issue areas singled out for action

included aid and assistance, international trade and finance,

industrialization, technology transfer, and business practices.

Paradoxically, while the NIEO demands were reformist

in character and, if acted on, could stave off revolutionary ferment (as did

New Deal legislation in the United States in the 1930s), the general position

of the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations on the NIEO were negative.

European nations were more responsive to selected demands, like stabilizing

Third World commodity prices and imports into Common Market countries, but the

broad package of NIEO demands continued to generate resistance from the wealthy

nations, which benefited from the current system. Nabudere correctly

understands the interests of Third World leaders in the NIEO when he wrote

that:

“The demands of the petty bourgeoisie of third world

countries are not against exploitation of the producing classes in their

countries, but of the domination of their class by monopoly. The demands

therefore for reform—for more credit to enable the petty bourgeois more room

also to exploit their own labor and extract a greater share of the surplus

value. This is unachievable, for to do so is to negate monopoly—which is an

impossible task outside the class struggle” (Wadada D. Nabudere, Essays on

the Theory and Practice of Imperialism, London: Onyx Press, 1979, p.179).

Therefore, the NEIO, commodity cartels like OPEC, and

other schemes for marginal redistribution of the profits derived from the

international economy would not have gone beyond increasing the shares which

Third World ruling classes received from the ongoing economic system. Minimal

benefits to workers and peasants would accrue. Third World successes against

monopoly capital, however, served to weaken the hold the latter has on the

international system.

Also, while channeling Third World militancy in a

reformist direction, the NIEO and OPEC had the opposite effect of

generating a new militancy among masses of Third World peoples where it did not

exist before. Those workers, peasants, and intellectuals who gained

consciousness of their plight in global structural terms through their leaders'

UN activities came to realize that NIEO demands were not enough. They would

come to realize what Nabudere argued, namely that:

“in order to succeed, the struggles cannot be

relegated to demands for change at international bodies, mere verbal protests

and parliamentary debates, etc. Therefore demands for a new economic order are

made increasingly impossible unless framed in the general context of a new

democratic revolution; the role of the working class and its allies is crucial

to the achievement, in any meaningful way, of a new international economic

order” (180).

Conclusion

In a period of less than twenty-five years, the United

States had solidified a worldwide military alliance system, stimulated

integrated economic institutions based on monopoly capitalism, started the most

dangerous arms race in world history, and engaged in repeated acts of military,

political, and economic intervention in nations throughout the world.

Similarly, labor militancy was crushed at home. The U.S. public was mobilized

by rhetoric about "fighting communism," "liberating" Eastern

Europe, constructing a "new frontier," aiding in economic

development, stopping "wars of national liberation," and 'building

peace with honor. "

Paradoxically, in this same period many political

forces were emerging to challenge the economic, military, and political

hegemony of the United States. Intervention in Chile admittedly fit the pattern

established in Iran and Guatemala in the 1950s and the Dominican Republic in

the 1960s. Between Iran and Chile, however, the United States had lost a major

war to the Vietnamese people and was unable to forestall Marxist victories in

southern Africa. Even reform minded Third World ruling classes were making demands

on the United States and its allies that impinged on the free workings of world

capitalism.

The People’s Forum