Black History Month: Some Remembrances

Harry Targ

(A Rag Blog repost from July 18, 2011)

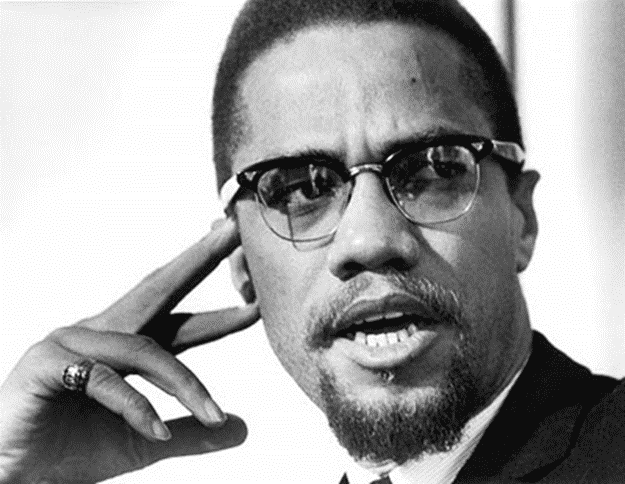

“And finally, I am deeply grateful to the

real Malcolm X, the man behind the myth, who courageously challenged and

transformed himself, seeking to achieve a vision of a world without racism.

Without erasing his mistakes and contradictions, Malcolm embodies a definitive

yardstick by which all other Americans who aspire to a mantle of leadership

should be measured.” Manning Marable, Malcolm X, A

Life of Reinvention, 2011, 493).

Manning Marable: Scholar/Activist

Professor Manning Marable was a member of the

Political Science and Sociology Departments at Purdue University during the

1986-87 academic year. His scholarship, activism, and ground-breaking books and

articles inspired faculty and students even though his stay at our university

was brief. His classic theoretical work, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black

America, along with over 20 books and hundreds of articles, inspired social

science scholarship on class, race, and gender.

His weekly essays, "Along the Color Line," were published in over 250

community newspapers and magazines for years. He once told me that writing for

concerned citizens about public issues was the most rewarding work he ever did.

He was a role model for all young, concerned and committed scholar/activists.

I just finished reading the powerful biography of

Malcolm X authored by Manning Marable. My encounter with this book was as

fixating and transforming as I remember my reading of Malcolm’s autobiography

in the 1960s.

On Malcolm X in the Classroom

While I lack the deep sense of Malcolm X’s impact on

African American politics and cultural identity that others have, I feel

compelled to write something about this reading experience. (Bill Fletcher’s

review and analysis of the Marable biography provides much expertise on the

subject. “Manning Marable and the Malcolm X Biography

Controversy: A Response to Critics," from The

Black Commentator, July 7, 2011.)

During my first year at Purdue University in north central Indiana in 1968, I

requested to teach a course called “Contemporary Political Problems.” Since I

was on the cusp of becoming a political activist in belated response to the

civil rights and antiwar movements, I thought I could use this course to have

an extended conversation with students about where we needed to be going

intellectually and politically.

My plan was to assign a series of books that reflected different left currents,

politically and culturally, and get us all to reflect on their value for

understanding 1968 America and what to do about it. We read Abbie Hoffman, Ken

Kesey, Herbert Marcuse, the Port Huron and Weatherman statements, and The

Autobiography of Malcolm X.

While my students and I embraced, endorsed, or rejected various of these

authors, we were profoundly impacted by the power of Malcolm X’s personal

biography and his transformations from the streets to the international arena.

As the word got out about the course, and largely because of Malcolm X, sectors

of the Purdue campus got the word that there was a new “radical” in the Political

Science department. (Therefore, I owe my growing enrollments to Malcolm X).

More important, during the second semester in which I taught the course, I had

a very quiet and respectful African American student in the class. He was a

member of Purdue’s track team. One day, after he showed up at the local airport

sporting a very thin, almost invisible, mustache the track coach ordered him

off the plane. Why? Because he had unauthorized facial hair. His modest

symbolic act, growing the mustache, and the universities response to his words

and deed, set off extended protest activities by African American students in

support of him over several weeks.

Shortly before this incident, we had spent a couple of weeks in class

discussing Malcolm X’s autobiography. During one class period this very quiet

person announced to the rest of us that we should consider ourselves lucky that

he chose to participate in this class.

I saw him 40 years later for a fleeting moment. He remembered me and said that

he had read Malcolm X’s autobiography for the first time in my class. The

student’s emerging boldness and his articulated sense of pride must have had

something to do with his reading of Malcolm X.

Manning Marable’s Biography of Malcolm X

Reflecting on the Marable biography, I was struck by

the capacity of people to change their ways of thinking, their ideologies, and

their practice. Marable attributes some of Malcolm X’s development to his

conscious desire to reinvent himself and to do so as he told his life story to

Alex Haley, his autobiographical collaborator.

Despite the world of racism, repression, and theological rigidity Malcolm encountered,

Marable records how Malcolm X’s experience and practical political work were in

fact transforming.

Different people gleaned different things from reading Malcolm X’s

autobiography, and the same is true of a reading of Manning Marable’s stirring

and frank biography. While those of us on the left were most inspired by the

last two years of Malcolm X’s life, my student was probably impacted as much by

Malcolm’s developing sense of pride and self-worth in a society that demeaned

and ridiculed people of color

Reading Malcolm and Marable reminds us that, while we bring change through our

organizational affiliations, each individual can have a role to play in

achieving that change. Not all of us can be Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Dolores

Huerta, or Mother Jones. But we can make a difference.

In addition, Manning Marable makes a particularly strong case for Malcolm X as

an internationalist. The United Nations had adopted a Declaration on Human

Rights in 1948 but human rights discourse was not part of the language of

international relations until Malcolm X demanded the international community

address the issue.

For Malcolm X, United States racism, while violating the civil rights of its

Black and Brown citizens, was also violating the fundamental human rights of

peoples at home and abroad. At the time of his assassination, Malcolm X

was working to build a coalition of largely former colonial states to demand

that each and every country, and particularly the United States, respect the

human rights of all peoples. Multiple problems including racism, poverty,

disease, hunger, political repression, and sexual abuse were problems at the

root of twentieth century human circumstance AND the United States was a major

violator of human rights.

Marable described in great detail Malcolm X’s frenetic travels through Africa

and the Middle East to build a coalition of Black and Brown peoples to demand

in the United Nations and every other political forum the establishment of

human rights. Bombing Vietnamese people and killing Black children in

Birmingham were part of the same problem.

And, this campaign was being launched at the very same time that the countries

of the Global South were struggling to construct a non-aligned movement to

retake the resources, wealth, and human dignity that had been stripped from

peoples by colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism. This was the position

that Dr. Martin Luther King came to in 1967, as articulated in his famous

speech at Riverside Church in New York. Malcolm X was introducing this global

human rights project in 1964.

Marable’s Malcolm X therefore transformed himself from a minor street hustler

to a Black Muslim to a visible world leader advocating a global human rights

agenda. This is the Malcolm X that has meant so much to us over the years,

along with his insistence that Black and Brown people be accorded respect

everywhere and that they should honor and respect themselves.

But, Marable carefully documents Malcolm X’s flaws as well as his strengths. He,

at various times, was anti-Semitic, misogynistic, not unsympathetic to

violence, and a man engaged in intense, sometimes petty, political struggles

with his organizational colleagues.

Manning Marable humanizes Malcolm X. Humanizing our heroes makes our efforts to

pass the messages and symbols of the past to newer generations of activists

more convincing. Young people do not need to see progressive heroes as

untainted by their own humanity. And when we present those who make a

contribution to building a better world to new generations, the examples of

their flaws make it clear that no one is beyond personal and political redemption.

Finally, the biographer, Manning Marable, as my statement at the outset

suggests, was a profoundly important scholar/activist. Marable used his

historical knowledge, social scientific analytical skills, and political values

to craft a career of writing and activism that impacted his students, his

academic colleagues, and his fellow socialists in the struggle for a better

world.

Telling Malcolm X’s story was Marable’s way of advocating for fundamental

social change in a deeply troubled world.